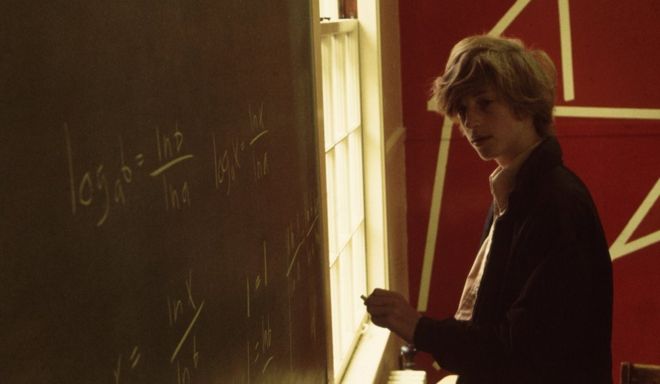

Image copyrightGates Foundation

Image copyrightGates FoundationMicrosoft founder Bill Gates talks in detail about his life to the BBC’s Kirsty Young on this week’s Desert Island Discs, on Radio 4 – from his schooldays (pictured above) to his latest work with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to “get rid of” diseases that kill young children.

Each castaway interviewed in the programme is asked to choose eight pieces of music, a book and a luxury item to take with them to a desert island.

Gates’s choices are listed at the bottom of the page, after some highlights from the interview.

At the age of 12, Gates explains, his parents sent him to see a psychologist.

“I was a bit disruptive. I started, early on, sort of questioning – were their rules logical, and always to be followed? So there was a tiny bit of tension there, as I was kind of pushing back. The [psychologist] they sent me to was very nice, and got me reading a lot about psychology and Freud and stuff like that. He convinced me that it was kind of an unfair thing that I would challenge my parents and I really wasn’t proving anything. So by the time I was 14 I got over that, which is good because then they were very supportive as I started to really engage in writing software and learning different computer things.”

Paul Allen, who would later become a co-founder of Microsoft, was a couple of years above Gates at school. Together they fixed the school scheduling software to ensure Gates was the only boy in classes of girls.

“Paul did the computer scheduling with me. Unfortunately for him he was two years ahead of me and he was off to college by then. So I was the one who benefited by being able to have the nice girls at least sit near me. It wasn’t that I could talk to them or anything – but they were there. I think I was particularly inept at talking to girls, or thinking, ‘OK – do you ask them out, do you not?’ When I went off to Harvard I was a little bit more sociable. But I was below average on talking to girls.”

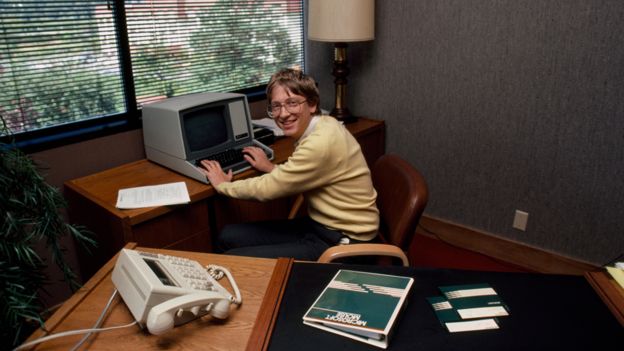

Image copyrightAlamy

Image copyrightAlamyGates dropped out of Harvard aged 19 to start Microsoft with Allen.

“Paul and I had done enough programming things – including our high-school scheduling – that we saved some money. So we just funded [the company] ourselves and had enough to hire a few people. We got to make a lot of mistakes because it was all new. How do you go do business in Japan? I’m hiring people who are older than me, and I can’t even rent a car because I’m not 21 years old. So it was really frantic.”

At one point, Gates confesses, he lost his licence for speeding.

“I’m well over that. But back then my first car was a Porsche 911. One of my few indulgences was that, at night, to think about our strategy, I’d go out and drive my Porsche up in the hills.”

“I worked weekends, I didn’t really believe in vacations,” Gates says of his early years at the helm of Microsoft.

“I had to be a little careful not to try and apply my standards to how hard [others at the company] worked. I knew everybody’s licence plate so I could look out the parking lot and see, you know, when people come in. Eventually I had to loosen up as the company got to a reasonable size.”

Image copyrightEPA

Image copyrightEPAListen to Desert Island Discs, presented by Kirsty Young, on the BBC iPlayer

Kirsty Young asks Gates if he was ruthless in business.

“No, only if you define having super-low prices as ruthless. It’s hard to compete with somebody who’s betting on the volume and saying, ‘Hey, we’re going to have… these super-low prices.’ That’s very intimidating and in that sense, yes we were aggressive.”

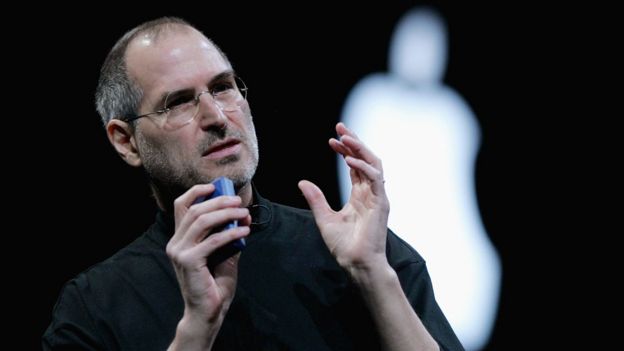

Image copyrightGetty Images

Image copyrightGetty Images“Steve really is a singular person in the history of personal computing in terms of what he built at Apple. For some periods, we were completely allies working together – I wrote software for the original Apple II. Sometimes he would be very tough on you, sometimes he’d be very encouraging. He got really great work out of people.

“In the early years, the intensity had always been about the project, and so then [when] Steve got sick, it was far more mellow in terms of talking about our lives and our kids. Steve was an incredible genius, and I was more of an engineer than he was. But anyway, it was fun. It was more of a friendship that was reflective, although tragically then he couldn’t overcome the cancer and died.”

Gates describes the first time he met the woman who would go on to become his wife.

“There was a Microsoft meeting in New York and I was the second to last one to come, and I sat down, and she was the last one to come. She sat down next to me and I asked her if she wanted to go out dancing that night, and she had some other people she was going off with. So then a few weeks later I saw her in the parking lot and I said, ‘Hey could you go out in a couple weeks?’ and she said, well that wasn’t spontaneous enough for her.”

Image copyrightGetty Images

Image copyrightGetty ImagesNeither of them thought at first their relationship would become serious.

“I was still being fanatical… I was willing in my twenties and most of my thirties to say the job was the centre of my life. Therefore I wasn’t going to get married or have kids. But I knew that eventually I wanted to, and she arrived at kind of the perfect time, and we fell in love. I had to think about it a little bit, but I said, ‘Yeah I want to change my priorities.’ And you know now we actually take quite a few vacations. I’m sure myself in my twenties would look at my schedule now and find it very wimpy indeed.”

Both Gates’s parents were involved in charities, including the birth-control organisation Planned Parenthood.

“It still is controversial in parts of America, that’s right. But my parents were both big believers in it. My dad was the head of that. So they set a very good example of being engaged in giving back.”

Gates says that for him and his wife the big thing is getting rid of the diseases that kill children under five, and spending their money in the “most impactful way”.

“I mean, you’re not going to spend it on yourself. And we think only a small portion should go to our kids, so that they can have their own careers and make their own way. And so that leaves most of it for Melinda and I to work on how should it be spent for the most needy in the world,” he says. “After a trip to Africa, we really started learning about disease… We were stunned to realise that for each $1,000 we gave, if we did it the right way, we could save a life.”

Image copyrightGetty Images

Image copyrightGetty Images